Introduction

The title of this lecture, like others I have used, is founded on a parable, in which language they often talk in the Eastern countries: in Mesopotamia, in Palestine, and in the lower valley of the Euphrates River. The Saviour's parables are but the common language of the people there. They converse in figures and symbols, in stories and parables, and one of the most beautiful truth-carriers that I ever heard is that of the "Angel's Lily."

The title of this lecture, like others I have used, is founded on a parable, in which language they often talk in the Eastern countries: in Mesopotamia, in Palestine, and in the lower valley of the Euphrates River. The Saviour's parables are but the common language of the people there. They converse in figures and symbols, in stories and parables, and one of the most beautiful truth-carriers that I ever heard is that of the "Angel's Lily."

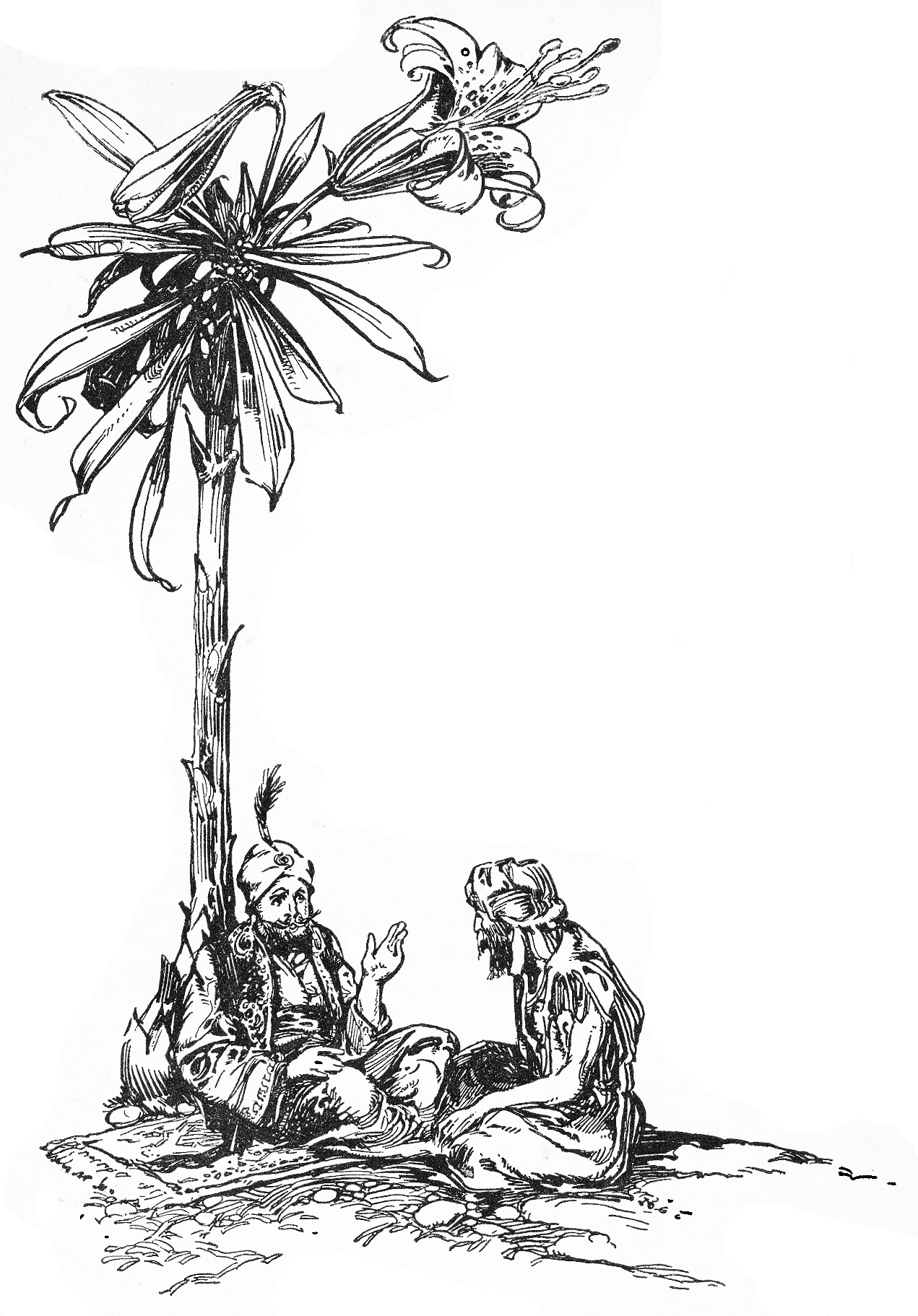

We were traveling down from Bagdad, with the same guide who composed the "Acres of Diamonds," and the English people connected with the English consulate rode out from the city to see us start down the river. They waved their hands after us and shouted: "Stop at the Angel's Lily! Stop at the Angel's Lily!" I had never heard of the parable before, and I asked the old guide what it meant. He said that he would tell us when we went into camp that night, and so, as we gathered around the camp-fire, after our humble meal, on the shore of that ancient river, the old guide, ancient patriarch that he was, told the story with intense interest, as though it was something of vast importance to him and as heartily as though he had never mentioned it before. I cannot repeat it as he did. The tears started in the corner of his eye. I have not the power to bring your imagination out so as to get a full vision, nevertheless its fascination remains with me. I wish you had heard him tell it! The lesson would be far more useful to you. But the old guide told us that the best wish one could give to any person one loved was to wish that they would "Stop at the Angel's Lily"; hence it was a very common form at parting to say, "Stop at the Angel's Lily!" And especially would a patriarch father, when parting with his children, wish them to "Stop at the Angel's Lily!"

Russell Herman Conwell

November, 1920

The Angel's Lily

There once lived at Bagdad a magnificent Caliph, rich, powerful, having an immense empire under his rule. He had all that money could possibly furnish. He was healthy, he had a large family, he was honored on every side, and lived in the most wonderfully decorated palace in all the East. Bagdad was the capital, and in that palace, ornamented with diamonds and all other forms of precious stones, he dwelt for nearly forty years. He had everything that the heart could possibly wish. He slept on beds of the softest down, he looked upon scenes of beauty made charming by art as well as by nature. He was not permitted to eat anything that was not prepared with the most delicate care. He was not allowed to hear a voice that was not modulated to musical tones, or to have a flower in his room which was not selected with the greatest care from the finest gardens of the country. He had everything that imperial power could command. No unsupplied need—he had everything that his heart could possibly wish—and yet he was the most unhappy man in all that land. He was weary of giving orders to armies; he was weary of having the responsibility of imperial authority; he was weary of seeing every person bow to the ground when he approached him; he was weary of so much care and nicety about the table and about everything that he ate. He was weary of having everything prepared for him in advance; weary of the beautiful carpets on which he trod; weary of having the best of everything, the most costly of everything; weary of all the wonderful ceremonies that went with his position. He went in and lay down upon his couch and prayed to the Ruler of Paradise that sometime he might be an unknown private citizen and have the comfort and rest of being simply himself.

On that same night, twelve miles down the river, at a little hamlet called Borzar, there was a beggar. He had been a hungry beggar for years. He was greatly afflicted in body; he was restricted in food and clothing; and he slept in an enclosure without a roof. And that very night he went into that enclosure and lay down in his rags upon the open ground, and, looking up to the stars, prayed to the Ruler of Paradise that he might some time have the comforts and luxuries of the Caliph of Bagdad.

On that same night the Ruler of Paradise called in two beautiful angels, and committing to their care the bulb of a lily, said to them: "Go down now with a heavenly reed, and measure carefully from the hut of the beggar at Borzar to the palace of the Caliph at Bagdad. Then measure half-way back, and there plant this bulb of the lily." The angels went down and measured from the hovel to the palace with heavenly nicety and then measured half-way back, and there they planted the lily on the banks of that river at that wonderful season of the year when all things were in glorious blossom. Then they separated, and one of the angels went down to the beggar at Borzar and said: "Beggar! wouldst thou be happy? Go to Bagdad." And at the same moment the other angel leaned over the sleeping Caliph of Bagdad and said: "Caliph! wouldst thou be happy? Go thou to Borzar."

Both rose, obedient to the heavenly summons, and started toward each other. They met halfway between the palace and the hovel, half-way between Borzar and Bagdad, and, as they met in the night-time, in that country they wished each other peace and sat down to converse together without asking of their antecedents. They sat down at that spot and were talking in friendly intercourse upon some interesting question that did not touch their personal life, when they saw the opening of the sand and a bright flash of light from the ground. As they watched the increasing light they saw the little green leaves of the lily's stem appear, and as it rose with magic increase of speed it finally unrolled into a beautiful, petaled lily, and the petals rose higher and higher, until they covered the whole horizon like a tent and shut in the Caliph and the beggar under the leaves of the magnificent flower. There they dwelt together in the most perfect peace, absolute happiness, and complete rest; no cares―everything that they needed was supplied and no more, and they dwelt together in loving-kindness; and when the lily disappeared they too were taken into the other world at the same moment.

Conclusion

So that tradition has come down through the ages, and whenever a friend wishes to express his loving farewell, he says, "Stop at the Angel's Lily!" When I heard that tradition (I took it down in shorthand in my diary), I studied upon it a long time before I could understand fully just what the old sheik meant. It was an illustration, a symbol; and as I studied long I found it reaching into all avenues of life, and, lo, it was one of the best descriptions of a philosophy of happiness that I ever saw put into any form, either in book or public speech. Because it is, after all, the place where men are happiest, half-way between Borzar, the hovel, and Bagdad, the magnificent palace of the Caliph. They learn the lesson easiest in the East, although they are not always contented there.